A ‘Parts List’ for cancer’s spread: Worms to fight metastasis

Cancer metastasis, the process in which cancer cells spread throughout the body, is a major challenge in cancer treatment and the leading cause of cancer-related deaths. Understanding how cancer cells break through tissue barriers and invade other organs is crucial for developing effective treatments. In a recent groundbreaking study, researchers at Duke University have utilized our favorite nematode C. elegans to create a comprehensive “parts list” of the cellular machinery involved in invasive cell behavior. The researchers stated that their work could potentially lead to new strategies for preventing cancer metastasis in humans.

The mystery of cancer metastasis

Metastasis is the process by which cancer cells detach from the primary tumor, penetrate the surrounding tissue, and migrate to distant organs. While numerous anti-cancer drugs have been developed, only a few effectively prevent metastasis, which is responsible for a staggering 90% of cancer deaths (Spano et al., 2012). The difficulty in studying this process lies in its unpredictability and the fact that cancer cells often metastasize to deep regions of the body, making them challenging to observe using conventional methods, such as light microscopes.

What does a tiny nematode have to say about cancer?

A while ago we already dedicated a blog post about C. elegans nematodes and their role in cancer research. In said article we highlighted that due to their relative simplicity (less gene families), genetic redundancy is reduced and it helps to unveil certain biological mechanisms that could potentially be translated into other animals and humans. Deregulation of energy metabolism, stem cell reprogramming and host-microflora interactions are some of the multiple cancer research lines that use our favorite nematode.

But what about metastasis? To overcome the challenges of studying cancer metastasis, the research team used C. elegans worms as they present a similar invasive process during their development. The worm possesses specialized cells called anchor cells that must break through a tough membrane to create a path for egg-laying. By studying this invasion process in C. elegans, researchers aimed to uncover the molecular mechanisms involved in cell invasion.

Unveiling the ‘Parts List’ of invasion

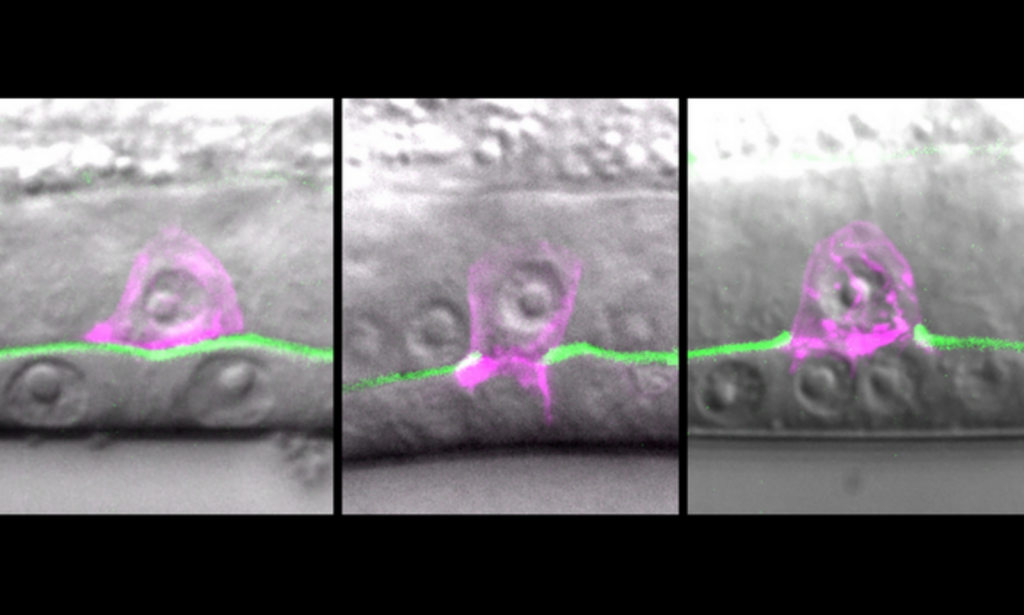

In their study, the scientists analyzed millions of transcriptomes (gene readouts) from invading worm cells to identify the genes and proteins responsible for invasion. They discovered approximately 1,500 genes that were significantly more active in invasive cells compared to other cells in the worm’s body. This comprehensive profile allowed the researchers to compile a catalog or ‘parts list’ of the cellular components necessary for invasion.

A key finding was the increased activity of genes encoding ribosomes, the cellular machinery responsible for protein synthesis. The researchers observed a surge in ribosome levels leading up to invasion, indicating the importance of protein production in facilitating invasion. By silencing specific genes related to ribosome production, the researchers observed a slowdown in invasive cell behavior.

A tiny worm cell hundreds of times smaller than a grain of sand is caught in the act of breaking through the tough outer membrane that normally holds cells in place. Source: The Sherwood Lab (Duke University).

This pioneering research offers crucial insights into the invasive behavior of cells, potentially paving the way for new strategies to impede cancer metastasis. By targeting combinations of genes that are involved in ribosome production and disrupting the supply chain necessary for invasion, researchers hope to develop novel approaches to halt cancer spread.

Cancer is still the second leading cause of death worldwide after heart disease (Global Health Estimates, 2016), and metastasis poses a significant challenge in the treatment of it. The study conducted by researchers at Duke University, employing C. elegans worms, has provided valuable insights into the molecular machinery underlying invasive cell behavior. This study represents a significant step forward in our understanding of cancer progression and offers hope for improved treatments and outcomes for cancer patients.

Furthermore, the scientists used fluorescent tagging to visualize the ribosomes and found that they congregated in an organelle called the endoplasmic reticulum, where protein synthesis and packaging occur. This clustering of ribosomes suggested a cellular strategy to boost protein production in preparation for invasion.